Introduction

In this blog post, we’re going investigate different floating point formats used in computers and how computers do calculations with floating point numbers. We’ll also describe floating point numbers in more detail and calculate the limits of various floating point number formats. Finally, we’ll write a program in C++ for calculating machine epsilon; the smallest gap between normalized floating point numbers.

History of the IEEE Floating Point Standard

Before the 1960s and 1970s, computers from different vendors did floating point arithmetic differently. So engineers and computer programmers had to consider the pros and cons of their computers’ different floating point formats. In 1976, Intel began to design a new floating point standard for their i8086, i8088, and i432 microprocessors. Because Intel planned to sell many of these microprocessors, they wanted to ensure that numerical results were consistent across all of their machines. They enlisted the help of William Kahan, a professor in the department of electrical engineering and computer sciences at Berkeley, who had done work improving the popular Hewlett-Packard calculators. When other companies heard the news of Intel’s plans, they were concerned about innovation. The news of Intel’s plans convinced them to join a committee to create a single floating point standard. Representatives of several companies held the meetings under the backing of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE). The standard became known as the IEEE 754 standard. The latest standard was published in 2019 and includes information about arithmetic formats, rounding, and exception handling.

Floating Point Numbers

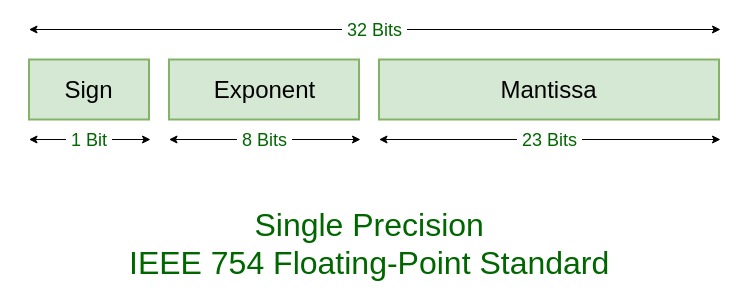

Floating point numbers are positive or negative numbers with a radix point (the binary point in base 2, the decimal point in base 10, etc.). Similar to scientific notation, floating point numbers separate a certain number of significant digits (called the significand or mantissa) from the magnitude of the number. Computers use a fixed number of bits to represent floating point numbers. For the IEEE 754 format, we allocate one bit for the sign (negative or positive), eight bits for the exponent, and 23 bits for the mantissa. We generally represent floating point number systems using the following notation:

\[F(\beta, t, m, M)\]In this notation, \(\beta\) is the base of the number system, \(t\) is the is the length of the mantissa, \(m\) is the minimum exponent, and \(M\) is the maximum exponent. The image below is a picture of the bit allocations for each part of the single precision IEEE-754 standard.

|

|---|

| Source: www.geeksforgeeks.org/ieee-standard-754-floating-point-numbers/ |

Normalized Floating Point Numbers

We write normalized floating point numbers such that the first bit of the mantissa is nonzero. The normalized floating-point looks like:

\[(-1)^s*(1.f)*2^e\]In this notation, \(s\) is the sign bit, \(f\) is the mantissa, and \(e\) is the exponent. The mantissa is assumed to have a “hidden” one, shown as \(1.f\). Because the first bit of the mantissa is one, we end up gaining an extra bit!

Range of Normalized Floating Point Numbers

Now, let’s investigate the range of possible normalized floating point numbers. Let’s say we have a 32-bit machine with the following floating point format: \(F(2, 25, -64, 63)\). The minimum positive number in this system would be:

\[(1.000000000000000000000000)*2^{-64}=2^{-64}\sim 10^{-20}\]This number has a mantissa with 24 zeros (remember, the first bit is equal to one) and an exponent of \(e=m=-64\). The maximum normalized floating-point number would have a mantissa with all ones and an exponent of \(M=63\). The maximum number in this floating point format is:

\[(1.111111111111111111111111)*2^{63}=\Big(1+\sum_{i=1}^{24}2^{-i}\Big)*2^{-64}\] \[=\Big(2-\frac{1}{2^{24}}\Big)*2^{63}=2^{64}-2^{39}\sim 10^{19}\]Now, let’s find a general formula for the range of representable positive normalized floating point numbers. So, using \(F(\beta, t, m, M)\) the minimum number is \(2^m\) and the maximum number is:

\[\Big(1+2^{-1}+2^{-2}+...+2^{-(t-1)}\Big)*2^M=(2-2^{1-t})*2^M=2^{M+1}-2^{M-t+1}\]So, the range of positive floating point numbers is \([2^m,2^{M+1}-2^{M-t+1}]\).

Using this formula on the IEEE 754 single and double precision formats: \(F(2, 24, -126, 127)\) and \(F(2, 53, -1022, 1023)\), we get \([2^{-126}, 2^{128}-2^{104}]\) and \([2^{-1022}, 2^{1024}-2^{971}]\), respectively.

Machine Epsilon

Machine epsilon \(\epsilon\) is the gap between one and the next larger floating point number. This definition is why the while loop condition in our program fails. The epsilon variable becomes \(\frac{\epsilon}{2}\). And \(1+\frac{\epsilon}{2}\) is not large enough to get to the next floating point number. From the program below, we get:

\[\epsilon=2^{-23}\]In general, \(\epsilon=\beta^{1-t}\). So this value is dependent on type of floating point system that’s used.

int eps(void)

{

int counter=0;

float eps_=1;

while(1+eps_>1)

{

eps_/=2;

counter++;

}

return counter;

}

Why do we need a counter in the program?

If machine epsilon is \(2^{-k}\), then \(counter=k+1\). For example, for the IEEE 754 format, the counter’s value is 24. When the counter is equal to 23 and epsilon is equal to machine epsilon, \(1+\epsilon\) is still a valid floating point number. So, the while loop is executed another time, after which the counter is 24 and the epsilon variable is \(\frac{\epsilon}{2}\). At this iteration, the condition \(1+\frac{\epsilon}{2}>1\) becomes false.

So, we need a counter in the program because otherwise we wouldn’t have any insight into the program. The counter allows us to calculate the exact exponent of machine epsilon.

Why are we dividing by 2?

We divide by two to ensure that there is no round-off error in our calculations. Dividing by two amounts to shifting the binary point. If we were to divide by three for example, then after the first iteration of the while loop, we would have to round our floating point number representation of \(\frac{1}{3}\). This is because \(\frac{1}{3}=(0.\overline{01})_2\) is an infinitely repeating binary number.

Conclusion

Thank you for reading this post! We’ve learned quite a few things! We learned about how floating point formats are used in computers. We also learned the limits of various floating point number formats. We also learned about machine epsilon by writing a C++ program to calculate it. I find the topic of floating point numbers interesting. So more blog posts to follow!